How the state buries cases of honour-killing

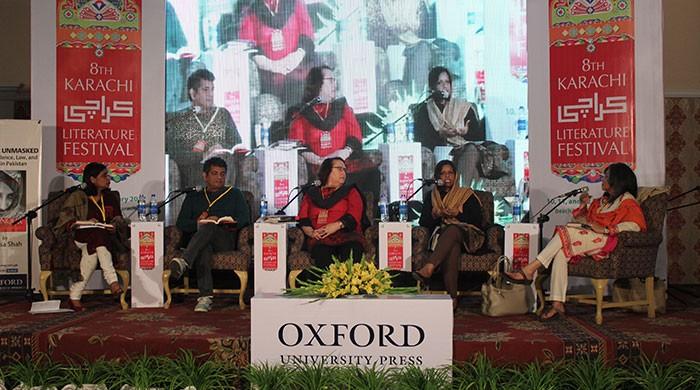

Nafisa Shah who recently penned a book on honour killing in Sindh was among the speakers

February 11, 2017

KARACHI: Patriarchy puts a man’s needs before a woman’s. In Pakistan one could blame it for rampant incidents of honour killings which last year claimed numerous lives, including those of social media star Qandeel Baloch and British-Pakistani Samia Shahid.

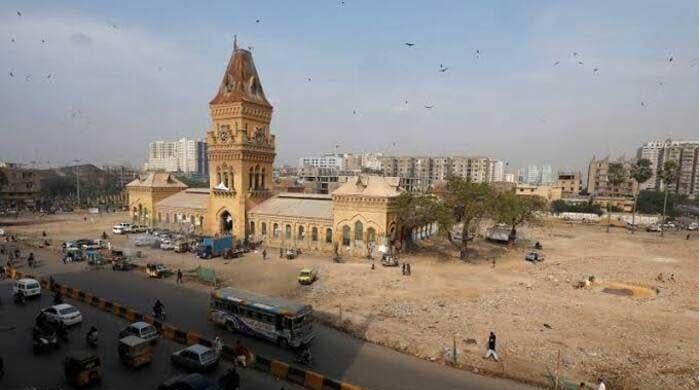

What makes a man kill a woman in the name of honour? The issue was discussed at a session titled “No Honour in Honour killing: Gender Violence, Law, Religion and Power in Pakistan” at the Karachi Literature Festival held at the Beach Luxury Hotel on Friday.

Among the speakers on the panel was parliamentarian Nafisa Shah who recently penned a book on cases of honour killings that took place in upper-Sindh. Shah argued that it was wrong to solely blame antique traditions for honour killings because the state is also partially responsible for the scourge.

She shared a chilling case of honour killing with the audience that took place in Shikarpur. Two girls-Abida and Tehmina - who had fled their homes were hunted down, killed and buried by their families.

After protests by human rights activists the case was brought to the courts, and after lengthy discussion which included looking for the bodies and conducting a post-mortem on them, the case was dismissed by the judge over “benefit of doubt”.

She claimed that girls were buried for a second time and “this time by the state”.

Anita Weiss, a professor at the department of international studies, University of Oregon said that one needs to delve into the historic practices which lead to such cases.

“For example,” she said, “where a woman goes, if she use a mobile or not, or if she goes to office, is decided by her husband or men she is associated to—even though [all of these actions] are considered a social norm in most parts of the world.”

She spoke about the recent murder of a social worker Hina Shahnawaz killed by her paternal cousin in Kohat, allegedly, for stepping out of her house and becoming the sole breadwinner for her family.

Weiss said that it was time people in Pakistan speak out against the heinous practice.

Also among the panelists was renowned author Muhammad Hanif who observed how honour killing was no longer a rural phenomenon and it was taking place in urban-centres such as Faisalabad and Jhelum. As an afterthought he added that as more and more women are making it to the workforce and getting economically independent honour-killings in cities have risen.

He recalled when he and Nafisa Shah were reporters at Newsline magazine, Shah worked on an honour killing story from upper-Sindh. “The words Karo Kari which went in the headline were unfamiliar then among the English-speaking class. That no longer is the case.”

Hanif said that single-column news stories of women who die in mysterious circumstances- packed in a suitcase, suffocated and strangled—are a daily occurrence.

He then questioned Shah, who is also daughter of the former Sindh chief minister Qaim Ali Shah, if she had directly intervened to solve a case while she was working on the book.

Shah recalled an instance when a woman sent a letter through a secret messenger and got it published in Sindhi daily Kaawish. “The letter addressed me directly and stated that if she get killed I will be responsible.” It was a case of forced marriage, she explained, and the woman finally got a divorce and legal aid.

She elaborated that in the absence of state institutions many times tribal chiefs in Sindh give refuge to honour killing victims in their houses. “The only problem is that once out of their protection they go back to the same community and risk getting killed.”

Darul-Aman, shelter homes for women, she claimed, were after all weak institutions that often treated victims like prisoners.