Matric is failing our children

During school years, Abdullah Naseem was a celebrated student. He scored up to 78 percent in his matriculation exams. Unconditional offers and scholarships from some of the best colleges in the...

March 29, 2017

During school years, Abdullah Naseem was a celebrated student. He scored up to 78 percent in his matriculation exams. Unconditional offers and scholarships from some of the best colleges in the country began flooding his mailbox. Naseem had a promising future. Or so he thought. In the real world, the festivities came to a screeching halt. The 25-year-old watched, ruefully, as others, with O Levels qualifications, whizzed past him up the ladder of professional growth.

He remained at the same desk, with the same paycheck, year after year.

"I was a winner,” he tells Geo.tv, "But after matric, I wasn’t. Those with O and A Level degrees were so far ahead of us that I had to give up.

But Naseem still had a choice. With the financial help of his family, he is now setting up a real estate business venture in the suburbs of Lahore. For other matric students, from middle and low-income backgrounds, there are few options.

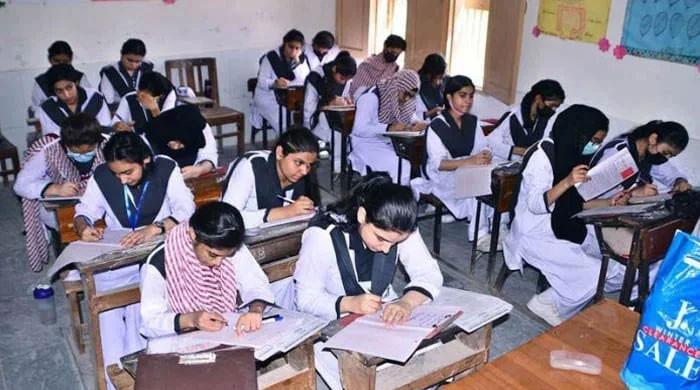

It is not their fault. Pakistan’s lacklustre education system has failed them. The Matriculation form of education has aged, declined and is now broken. It’s a relic of the past, passed on from the British Empire and still retained by Pakistan and India. Even Britain has reformed and replaced Matric with the Ordinary and Advance Level Examinations, which are offered in a select few private schools in Pakistan. Majority of school-going children still sit for their Matric papers to be graded by state-run education boards.

Matriculation offers a rote form of learning. Knowledge soaked up through its curriculum can only take students so far. This further increases the gap between the children who appear for international exams – such as O and A Levels – and those who sit for local ones.

When these children enter the corporate world, the bias is clear. Saima Bilal, who heads the Al Falah Insurance’s Human Resource Department, agrees that a child’s qualification quickly determines where he would end up in an organization. "In general, we tend to select those with A-Levels for strategic jobs, such as research and development; and those with Matric for industrial or field jobs,” she says, "Matriculates are usually street smart. They can deal with the labour, which is why we tend to place them in the field. Cambridge graduates have superior communication skills, and thus we tend to place them in jobs where communication matters more.”

In other words, O Level graduates are presentable, articulate, and eventually secure better pays.

Matric students earn 15 to 20 percent lower when starting off at a firm. "Even though Matriculates form the bulk of the workforce, HR departments tend to choose Cambridge students for mid-tier to senior-level jobs,” Ayesha Lari, Deputy General Manager Human Resource at Interwood Mobel, tells Geo.tv.

Matric has few advantages. It is outdated, with a curriculum that hasn’t been reformed and reinvented in years. Why do students still opt for it? The answer lies in the finances. The fee for Lahore Board’s Matric exams this year is under Rs.1200. While, O Levels can cost Rs.80, 000 – for the mandatory eight subjects students are required to take.

"Matric is nowhere near being obsolete,” insists Mosharraf Zaidi, heading Alif Ailaan, a political campaign to address Pakistan’s education crisis, "Simply because of the numbers. We are talking millions, who take Matric, vs. thousands” who appear for O & A Levels in Pakistan. The difference in numbers is indeed staggering. Last year, 270,000 students registered for Cambridge exams from all over Pakistan. In the same year, 216,692 students registered for matriculation from the Lahore Board alone. However, Zaidi does acknowledge that the system cannot continue as is. "Some of the necessary changes that need to be made are being made since 2013, especially with the teachers. What needs to change is that most people do not have much confidence in government schools.” Matric cannot end, he further adds, because if everyone starts getting Cambridge certifications it will lose the premium that is currently attached to it in the country.

One suggestion, often floated by educationalists, is a complete overhaul of the Matric system, by replacing it with a new local board and curriculum. "We need to develop alternate boards that are affiliated with our own universities, such as the Lahore University of Management Sciences,” says Tariq Waheed, a teacher at a private school, "Why must we send out money to England every year? Why can’t we develop a system that incorporates the best of O levels and Matric?” An example of this already exists in Pakistan, known as the Agha Khan Examination Board, which is affiliated with Agha Khan University in Karachi. This system is similar to the Cambridge system in its approach - with goal oriented teaching, sequenced curriculum and clearly defined learning objectives. This unique teaching method allows them to produce far more competitive students than do provincial boards.

Will then Pakistan take a cue from the Agha Khan University? Or can Matric be saved?

The author is a producer with Geo News based in Lahore.