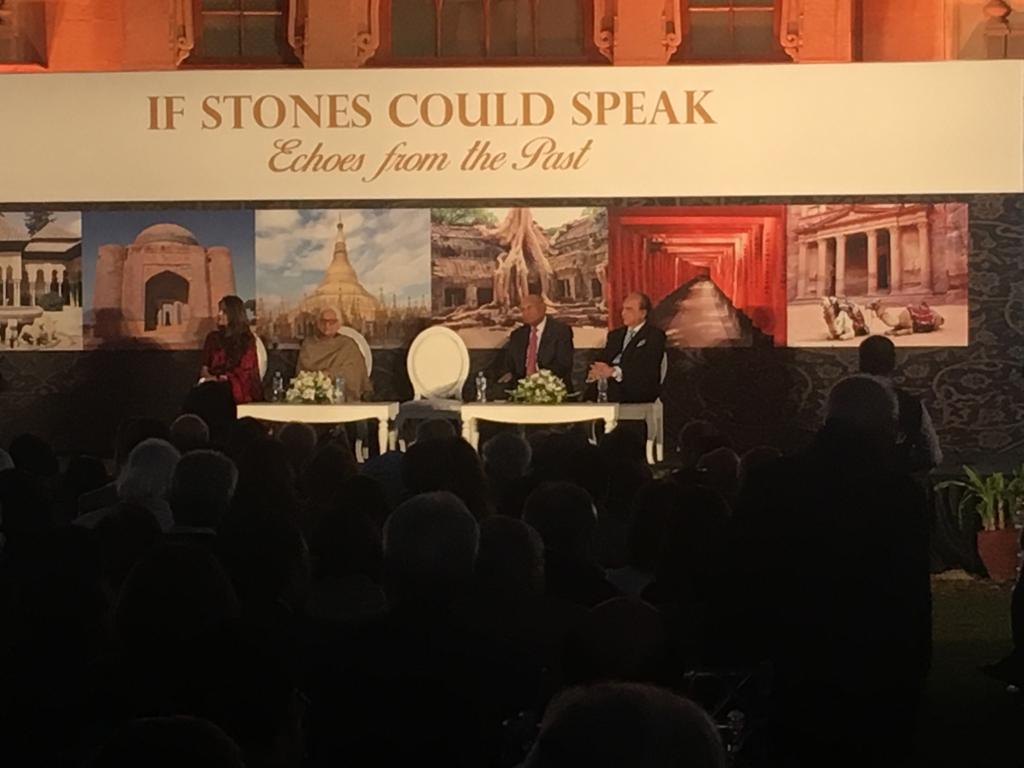

Book review: If Stones Could Speak

The book vividly illustrates the background of some of the giants of Muslim and other civilizations

January 28, 2019

It is indeed an honour and a pleasure to comment on this remarkable work by Doctors Iftikhar and Naseem Salauhuddin, two very good friends whom my wife Khadijah and I have had the privilege to know for some four decades.

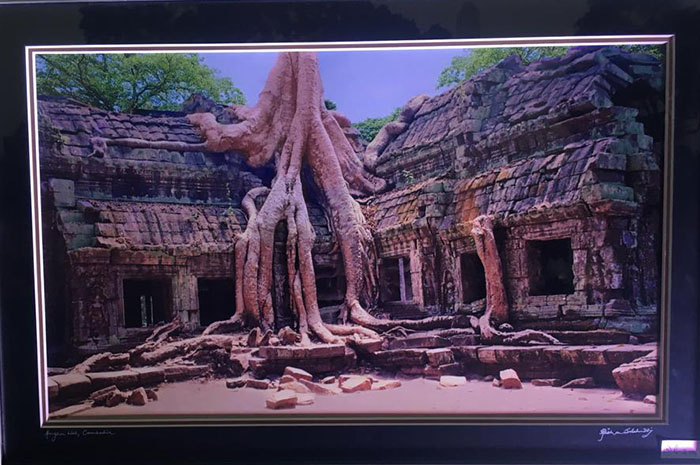

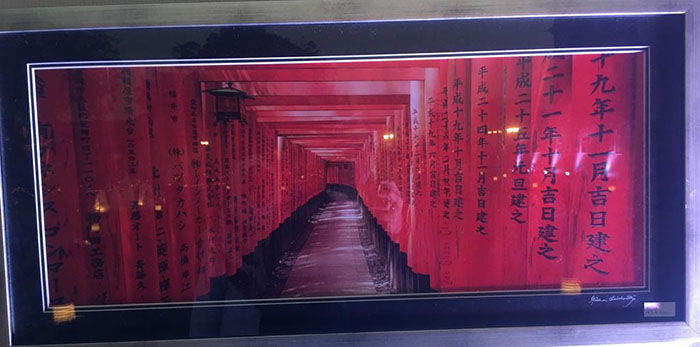

During my early interactions with these two physicians, I was unaware they were also passionate travellers, photographers and writers. That fact dawned on me much later when I saw their early publications. I marvelled at how they could find the time and above all the motivation to painstakingly document their travels so that those of us unable to visit Jerusalem, Persepolis or the great mosque of Xi’an could listen to their stones speak to us. All these tales are narrated in their latest and possibly the most accomplished book ‘If Stones Could Speak’. This book, I might add is not a travelogue. It is a well-researched work on monuments, autocrats and great scholars of yonder, whose scholarship is backed up by more than 100 bibliographic references.

As Prof Akbar Ahmed notes, this book “is a fascinating look at some of the world’s most beautiful historical sites, in the form of bite-sized travelogues and observations about the wealth of the planet’s archaeological, historical and cultural heritage”.

In making these stones speak to the reader, Iftikhar and Naseem have also evoked respect and awe for the rulers, builders and thinkers of the eras gone by.

Many of us are familiar with these monuments because we have read about them or seen them physically. Through their illustrated lessons, the authors have educated us about the autocrats who through their ruthless and occasionally benign rule changed the course of world history many times.

Even more important for me, in the chapter titled: Footprints On History, in which Naseem and Iftikhar have brought to life the big thinkers in history who have shaped our thoughts over the centuries. It is the stories and photographs of these thinkers in this book that I am most impressed by. They remind us that while kings and generals conquered and left their legacy in stones, it is the thinkers and teachers whose legacies will live in our minds and in our hearts forever. Their legacy will not be weathered or eroded by time like the monuments built with stones.

My personal favourite chapter of the book is The Great Central Asian Scholars.

It’s the Central Asian “stones” under this chapter that speak to me the loudest. Possibly because I have been living there over the past five years and have come to know better the people of this region and about their history.

We learn about Abu Ali Ibn Sina the 11th century Persian, Somoni philosopher and physician, and his famous line: “I prefer a short life with width to a narrow one with length.” He is the one who discovered and carefully illustrated the human blood circulation system. When eventually Ibn Sina’s magisterial Canon of Medicine was translated into Latin, it triggered the start of modern medicine in the West and became its Bible: a dozen editions were printed before 1500.

To my astonishment, and contrary to general belief, during my time in Central Asia, I learned that many of the learned Muslim philosophers, scientists, mathematicians, astronomers and social commentators were not Arabs but actually Central Asians. For example, I didn’t know that five of the six authorities who compiled the Hadiths of the Holy Prophet (Peace be Upon Him) were Central Asians. These were Bukhari from Bukhara now Uzbekistan, while Shahi Muslim, Tirmidhi, Abu Dawood and Ibn Majah were all from Persia what is now Iran, They were not Arabs at all.

In his recent authoritative book Lost Enlightenment, Fred Starr notes that “many if not most Western writings down to the present day identify” the great Muslim thinkers as Arabs. He goes on to explain that Ibn Sina (the father of modern medicine and great philosopher) was from Bokhara, Somoni Empire; Al Biruni (the founder of anthropology and pioneer of intercultural studies and comparative religions) was from Persia, Khwarazmi (founder of Algebra) from Uzbekistan, Al Farabi the remarkable political philosopher, metaphysics and ethicist was from Kazakhstan; Gazali (the religious philosopher) was from Persia. The giants of Muslim civilizations were not all Arabs but mostly from Central Asia and Persia. Western scholars assumed they were Arabs because these Central Asians wrote in Arabic, which was not only an advanced language but the lingua franca of that period.

Western writers and through them most of us in the sub-continent have also accepted that these were Arab scholars. Arabic was not their native language and nor were they Arabs. A Central Asian who wrote in Arabic a millennium ago was no more an Arab than a Japanese today who writes a book in English is an Englishman.

As Harvard Richard Frye has observed, “It is a remarkable fact that, with few exceptions, most Muslim scholars both in the religious and intellectual sciences were non-Arabs.

The book vividly illustrates the background of some of the giants of Muslim and other civilizations. The authors have done a valuable service by educating us about many of these historic facts through their beautiful narration and photographs personally taken over the years.