How safe is 'safe city'?

Crime is meant to be stopped before it spreads, but behind this glass lies something far more powerful than promise of public safety

August 26, 2025

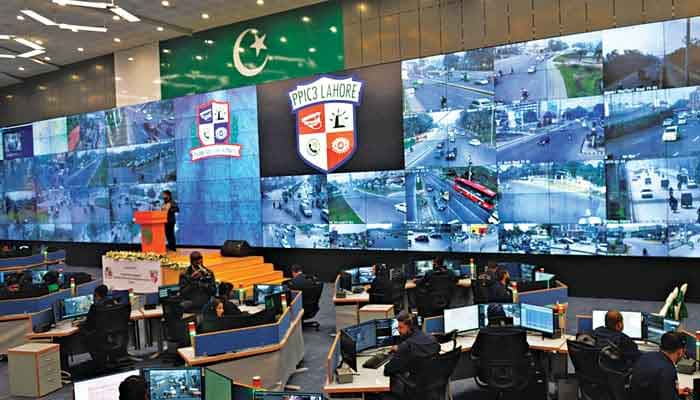

Lahore, winter morning. The Safe City control room hums under the fluorescent lights, a wall of screens showing every artery of the city in quiet detail. Faces flicker past in high definition; number plates are frozen mid-frame; a bank of operators zooms in on a man arguing with a traffic warden.

Here, crime is meant to be stopped before it spreads, but behind this glass lies something far more powerful than the promise of public safety.

The network these cameras feed into is one of Pakistan's most ambitious technological projects: the Punjab Safe Cities Authority's Integrated Command, Control and Communication Centre (PPIC3). But allegations and law suits say that this system could be — or may have been — mirrored far from home. Such a charge itself should have set every parliamentary committee alight.

Instead, the expansion rolled on. Lahore's Safe City deployment covers thousands of networked cameras, 8,000 of them monitored by over 400 staff in PPIC3, connected by some 2,000 km of fibre. The feeds come not just from fixed poles but from mobile units and vehicle cameras, funnelling into databases designed to integrate with license plate recognition and, increasingly, facial recognition.

That facial recognition layer is no longer theoretical. Nadra has begun national face verification, rolling it out on January 15, 2025, for use in registration centres and via the Pak-ID app. Officially, it is meant to help citizens whose fingerprints are unreadable. But combined with Safe City's real-time feeds, it lays the technical foundation for matching every face in public space to a national identity file.

What in other countries would be a targeted investigative tool here risks becoming a blanket mechanism for tracking, profiling and denying services without the citizen ever knowing. Karachi’s upcoming Safe City network is another leap.

The Sindh Safe Cities Authority has confirmed Hikvision facial recognition linked directly to criminal databases, along with automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) scanning every vehicle that passes. A "match" could send an alert to police in seconds. In the right hands, it could catch fugitives.

In the wrong ones, it could blacklist a political opponent or map the network of our politicians, bureaucrats, scientists and security personnel, which can be a significant threat to our national security and interests. The hardware will not care which.

The central problem is not the cameras, but the vacuum around them. Pakistan still has no enacted comprehensive data protection law.

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023, exists only as draft legislation. In its absence, there are no statutory safeguards for how long footage is kept, who can access it, under what conditions it can be shared or how citizens can challenge its use. The result is an inversion of the democratic sequence: surveillance first, law later — maybe.

Most critically, beyond this, there is the vendor question. And the core governance question remains: Who, outside Pakistan, can log into these systems today? Without independent audits, master admin keys and complex in-country storage rules, access becomes a matter of contractual fine print, not constitutional control.

It is easy to see how these systems can drift. In law-enforcement briefings, they are "force multipliers". In human rights analysis, they are "function-creep machines". A Safe City feed that spots stolen cars can just as easily flag every vehicle that attends a political rally.

Facial recognition technology that identifies wanted suspects can also be used to track every lawyer entering a courthouse or every journalist visiting a whistleblower. Without hardcoded legal walls, the slide from public safety to political surveillance is not a leap; it is a step.

The academic literature on surveillance colonialism warns precisely about this blend of dependency and opacity. When a country’s security infrastructure depends on foreign technology stacks that it cannot independently inspect, its data can become a strategic export without formal trade. Whether the ‘backdoor’ described in the BES complaint exists is less important than the fact that our current procurement model could allow one tomorrow.

This is not only a privacy issue, but also a sovereignty one. Safe City systems are already in Lahore, Islamabad, Multan, Faisalabad, Quetta and Peshawar. Islamabad is adding 3,100 new cameras. Karachi's buildout runs into the tens of millions. Each new pole camera is another lens that can, in theory, be piped elsewhere in real time if the architecture allows. Without law, without audit, without public reporting, the citizen is simply asked to trust that it will not be.

To fix this, Pakistan needs to invert the sequence. Before another camera goes up, there must be binding law that imposes purpose limitation so that footage can only be used for specific, legally defined investigations, retention limits so that raw footage is deleted after a set period unless tied to an active case, independent oversight through a supervisory authority with audit rights over every Safe City instance, tamper-evident logs ensuring every access to the system is recorded and reviewed, and air-gapped backups with all core data stored physically within Pakistan under independent key control.

Other democracies have done this. The UK's Surveillance Camera Code of Practice, the EU's GDPR and even parts of India's DPDP Act place statutory limits on automated surveillance. Pakistan is installing one of the most extensive urban monitoring networks in the region without any equivalent guardrails.

There is still time. Parliament can summon the Punjab Safe Cities Authority, Sindh Safe Cities Authority, NADRA and the Ministry of IT for a joint hearing. Civil society can demand that procurement contracts be published with redactions only for passwords, not for system architecture. Technical experts can be appointed to carry out penetration tests and verify whether any remote access pathways exist.

If nothing changes, the precedent will harden: our streets watched by systems we do not fully own, our biometric identities linked to our movements, our movements potentially accessible to parties we cannot see.

In the BES complaint's own words, the alleged duplication created access to data ‘important to Pakistan's national security’. Whether or not a judge agrees, the warning is plain: the power to watch is the power to rule. The operators in that control room will keep watching. Their lenses will keep narrowing in on small acts and big ones. The screens will glow, steady and silent.

The real question is: who else might be watching them glow from outside of our state, tracking our politicians, mapping our security personnel and tracking our sensitive movement? Only time will tell.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

The writer is the director of the Centre for Law, Justice & Policy (CLJP) at Denning Law School. He holds an LLM in Negotiation and Dispute Resolution from Washington University.

Originally published in The News