The Faiz we wish for vs the Faiz we got

The choice between the Faiz we wish for and the Faiz we got is, ultimately, a choice between two futures

December 20, 2025

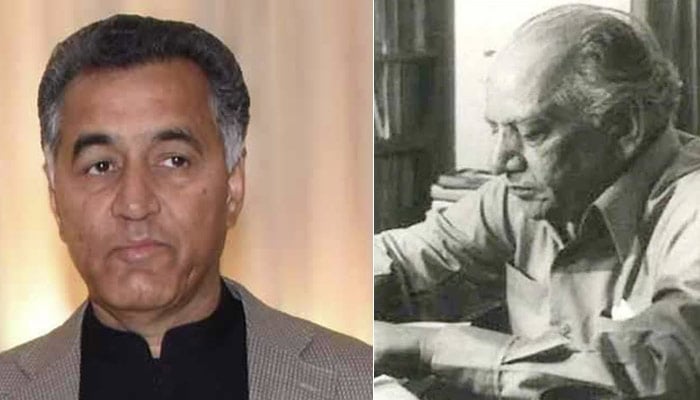

Names carry histories, hopes and sometimes cruel ironies. The name ‘Faiz’ evokes two vastly different legacies that stand at opposite ends of our political and moral imagination. One is Faiz Ahmed Faiz — Faiz Sb to many like us who loved him. A poet of compassion and resistance whose verses gave courage to the oppressed and language to hope.

The other is General Faiz Hameed, a powerful intelligence chief whose tenure became synonymous with control, coercion and the narrowing of democratic space. Placing these two figures side by side is not merely to compare two individuals but also to reflect on two competing visions of Pakistan.

Faiz Ahmed Faiz belonged to a tradition that believed words could shake thrones — a progressive, revolutionary poet who wrote against injustice, tyranny and the cruelties of unchecked power. His poetry was not abstract rebellion; it was rooted in the lived realities of workers, political prisoners, exiles and those silenced by the state.

At a time when military dictatorships cast long shadows over Pakistan’s politics, Faiz Sb’s verses circulated like contraband hope. They were memorised, recited at protests, whispered in jail cells, and sung at gatherings of political workers who believed another Pakistan is possible. Though he too at times showed despair — “ye daagh daagh ujala ye shab-gazida sahar/vo intizar tha jis ka ye vo sahar to nahin”.

What made Faiz Sb extraordinary was not only the fire of his poetry but the gentleness of his person. Many, including myself, who met him recall a kind-hearted, soft-spoken man whose humility contrasted sharply with the revolutionary force of his ideas.

This combination, compassionate humanity paired with uncompromising opposition to oppression, gave his work enduring credibility. He did not call for justice from a distance; he paid the price for his beliefs through imprisonment and exile. Yet even then, his poetry refused bitterness. It insisted that cruelty was temporary and that the night, however long, would eventually yield to dawn — “ummid-e-sahar ki baat suno”.

Once at our home, answering critical questions from a young student leader like myself on why he is not writing aggressively against General Zia’s tyrannical rule, Faiz Sb, with all his humility, smiled and said, “I will never bow in front of a dictator. He then recited his poem, “sitam sikhlaega rasm-e-vafa aise nahin hota/ sanam dikhlaenge rah-e-khuda aise nahin hota/ gino sab hasraten jo khuun hui hain tan ke maqtal men/ mire qatil hisab-e-khun-baha aise nahin hota”.

Faiz Sb’s appeal to the youth, especially political workers, lay in this moral clarity. He did not demand blind loyalty or a single narrative. Instead, he invited people to think, to question, to imagine — “jin ka diin pairvi-e-kizb-o-riya hai un ko/ himmat-e-kufr mile jurat-e-tahqiq mile”. His progressivism was expansive, embracing diversity of thought, culture and identity. In a country repeatedly subjected to authoritarian interruptions, Faiz Sb became a symbol of intellectual freedom. A reminder that patriotism does not mean obedience, and dissent is not treason.

Set against this legacy is the figure of General Faiz Hameed, whose name, for most Pakistanis, represents the opposite impulse: not only ruthlessly ambitious, but crude to the core as well. The few interactions I had with him shocked me at how he had reached this level.

As head of the country’s premier intelligence agency, he occupied one of the most powerful and opaque positions in the state. During his tenure, critics, journalists, political leaders and human rights defenders accused the security establishment of manipulating political outcomes, engineering elections and persecuting dissenting voices. Whether through overt pressure or subtle intimidation, the effect was the same: a shrinking space for dissent and democratic choice.

General Faiz’s critics contend that he embodied a mindset that prioritises control over consent and uniformity over pluralism. In this worldview, society must conform to a ‘fixed narrative’, deviations are treated as threats and institutions exist to enforce compliance rather than serve the public. Allegations of collusion with the then political leadership to maintain power and prolong influence became part of the public discourse, reinforcing the perception that democratic processes were being subordinated to strategic calculations.

Some have seen the widely reported and debated court-martial of General Faiz as accountability long overdue. Yet for many Pakistanis, the issue extends beyond the fate of one individual. The deeper concern is that the mindset with which he is associated persists. Censorship, suppression of dissent and the policing of opinion continue to shape public life. Journalists still face pressure, political activists still fear reprisals and diversity of thought remains constrained by invisible red lines.

This is where the contrast between the two Faizes becomes most stark. Faiz Ahmed Faiz believed that a healthy society depends on diversity of ideas, cultures, and voices. He trusted the people, even when they disagreed with him. His optimism was not naive; it was hard-earned and resilient. He understood that progress is uneven and setbacks are inevitable, but he refused to surrender the future to despair. His poetry repeatedly returns to the promise that oppressive systems, no matter how entrenched, are ultimately fragile — “jab zulm-o-sitam ke koh-e-giran/ ruui ki tarah urr jaenge”.

In contrast, the mindset attributed to General Faiz Hameed reflects a deep suspicion of pluralism. It treats dissent as disorder and difference as danger. In doing so, it impoverishes the national imagination. A society forced into a straitjacket cannot innovate, reconcile or heal. It may achieve temporary stability, but at the cost of long-term legitimacy and trust.

The tragedy for Pakistan is that, while we yearned for more figures like Faiz Ahmed Faiz — people who could guide us through darkness with empathy and courage — we found ourselves dominated by figures like General Faiz, who represent the machinery of control. It is an irony that borders on cruelty: the name that once symbolised resistance to tyranny now evokes, for many, memories of enforced silence.

And yet, the story does not end in despair. Faiz Sb himself taught us that history is not linear and power is never permanent. The ‘night’ may feel endless, but it is not eternal. His poetry continues to circulate, reminding new generations that hope is a form of resistance — “kahin to hoga shab-e-sust-mauj ka sahil/ kahin to ja ke rukega safina-e-gham dil”.

As long as his words are read, sung and believed, the alternative vision of Pakistan that he championed remains alive.

The choice between the Faiz we wish for and the Faiz we got is, ultimately, a choice between two futures. One is built on fear, conformity, and control. The other rests on justice, diversity, and the courage to imagine a better tomorrow. Pakistan’s fate depends on which legacy we decide to carry forward and which we finally leave behind.

Many believe this is no longer Quaid-e-Azam’s Pakistan but rather Gen Zia's Pakistan. Will it remain like this? In Faiz Sb’s words: “Hum dekhenge/ lazim hai ke hum bhi dekhenge”.

The writer is the managing editor of Geo News.

Originally published in The News