Chainsawed Islamabad

Abrupt and large-scale cutting of trees across Islamabad has triggered a rare wave of civic backlash

January 21, 2026

Trees are the custodians of life. Long before climate treaties, court orders or development plans, they sustained civilisations. Unfortunately, Pakistan’s brick-and-mortar mindset deems them expendable obstacles.

The abrupt and large-scale cutting of trees across Islamabad has triggered a rare wave of civic backlash. The official assurance that saplings would replace full-grown trees only deepened scepticism and raised troubling questions. Can young saplings realistically substitute the ecological functions of decades-old trees? Or is Islamabad’s natural heritage being sacrificed under the convenient cover of public health and legal compliance?

Shakarparian, once a beautiful green haven defined by dense canopies, now bears the scars of ruthless clearing. The justification offered is a Supreme Court directive aimed at eradicating paper mulberry, blamed for allergies and ecological harm. On the surface, the rationale sounds reasonable. Otherwise, an extreme response, it is akin to allaying Lahore’s suffocating smog by scrapping all smoke-spewing vehicles.

A scathing report by WWF-Pakistan reveals that Islamabad’s loss of vegetation extends far beyond the much-touted paper mulberry eradication drive. Unchecked infrastructure expansion has emerged as a major driver of deforestation. Field inspections conducted over the past year documented extensive tree clearing along Shakarparian, Sector H-8, the Islamabad Expressway and the Margalla Enclave Link Road.

The report points to deeper, systemic flaws, including weak transparency, poor site-specific ecological planning and inadequate monitoring. These deficiencies cast serious doubt on claims of environmental restoration. Safeguards such as phased removal, prior afforestation and rigorous ecological assessments that should have guided the process appear to have been ignored.

Islamabad is already suffering because of this approach. Rampant, concrete-driven development has steadily eroded the green buffers that once moderated temperature and filtered pollution. The unprecedented pall of smog that recently enveloped the capital, unthinkable just a few years ago, is not an aberration but a consequence of urban expansion without balancing the ecology.

Trees are critical climate infrastructure. They regulate temperature, absorb pollutants, stabilise soil and recharge aquifers. Even if the removal of paper mulberry was motivated by legitimate public health concerns, it demanded precision, restraint and scientific rigour. The cure, CDA-style, risks being far worse than the ailment it set out to treat.

Official figures underline the scale of the intervention. Approximately 12,000 paper mulberry trees have been removed from the F-9 Park, 8,700 from Shakarparian and thousands more from H-8 and other areas. Official figures quote a total of 29,115 felled trees; the real figure might be a far more morbid tale.

Authorities insist that the exercise was carefully supervised and fully compliant with Supreme Court directives. The government’s track record of honouring judicial decisions has been anything but impressive. No wonder the official narrative of submission to a court order has found few takers.

A judicial directive also cannot logically become carte blanche for rapid, large-scale tree destruction. Environmental jurisprudence is rooted in balance. Removal must be done only where absolutely necessary, with preservation as the guiding principle and with long-term survival of replacement trees ensured. What has unfolded in Islamabad suggests an approach far removed from this equilibrium.

The real danger lies in how legal directives are weaponised in Pakistan. Court orders invoked without context, nuance or restraint risk becoming tools of convenience rather than instruments of protection. They can also serve as smokescreens for vested interests. Once chainsaws are legitimised in principle, oversight weakens in practice. This becomes the conduit to misuse and corruption.

If places like Shakarparian, nestled in the heart of the capital, can be stripped so easily, what chance do Pakistan’s hinterlands stand? Tellingly, the backlash over tree felling in Islamabad contrasts starkly with the silence surrounding the blatant deforestation of Pakistan from the majestic forests of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Azad Kashmir to the dwindling mangrove swamps of Karachi. Builder and timber mafia operate with impunity as forests vanish without headlines.

Pakistan’s deforestation crisis, with our forest cover hovering at less than five per cent, sees 11000 hectares lost each year. We are paying the price as floods grow more destructive, heatwaves more lethal, droughts more persistent and landslides more frequent. Photo-op plantation drives and green slogans cannot compensate for this loss. Without protecting and increasing green assets, such campaigns, at best, are fallacies.

We rank among the most climate-exposed countries in the world. Bizarrely, this ever-increasing climate vulnerability is compounded by an absence of intent. As our green cover recedes and unplanned concrete expansion accelerates nationwide, cities are turning into basins of asphalt and glass where fumes linger and heat intensifies. The stakes have never been higher.

Pakistan requires a mammoth $566 billion over the next decade to meet its NDC 3.0 commitments, including emission reductions and a transition to renewable energy. Needless to say, no amount of funding will suffice if forests and urban green spaces continue to be treated as expendable. Climate targets cannot be achieved in conferences and policy documents while trees fall on the ground.

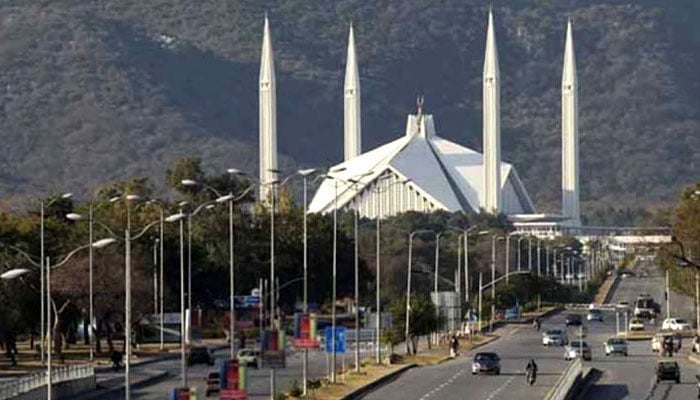

Islamabad, framed by the Margalla Hills, was envisioned as a city in harmony with nature. Its transformation into a smog-prone, overheated urban sprawl is an indictment; a failure of planning, governance and intent. Today, Islamabad’s denuded patches are more than physical scars; they epitomise our national abdication of environmental responsibility.

Trees are not decorative afterthoughts to development. When the din of chainsaws replaces birdsongs as they fall, cities overheat, air stagnates, water disappears and resilience collapses. Saving Islamabad’s trees and Pakistan’s forests is no longer a matter of aesthetics or idealism but one of survival.

Until intent replaces apathy and law is guided by its spirit rather than its loopholes, every chainsawed trunk will be yet another peg of an environmental disaster we can no longer afford.

The writer is a freelance contributor. He can be reached at: [email protected]

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

Originally published in The News