Charing Cross: A snapshot of Lahore's multicultural past

Charing Cross is a reminder of the multicultural and rich cultural and political history of Lahore

February 27, 2017

Tracing the century-old history of Lahore's Charing.

Battle of Gujrat, Lahore Durbar

Following the Battle of Gujrat in 1848, the East India Company annexed the province from the Lahore Durbar and made it part of the British Raj. After the disastrous War of Independence – a mutiny that the Imperialists brutally suppressed – Lahore grew as a seat of Colonial Punjab's administration.

The local cantonment, located in the tree-lined outskirts of north Lahore's Badami Bagh, was shifted just past the village of Mian Mir to a site free from the deadly mosquitos of River Ravi’s riverbed. A metalled road, most grandly called the Upper Mall, was aligned by 1860 to connect the expanding city with the new garrison.

Walled City

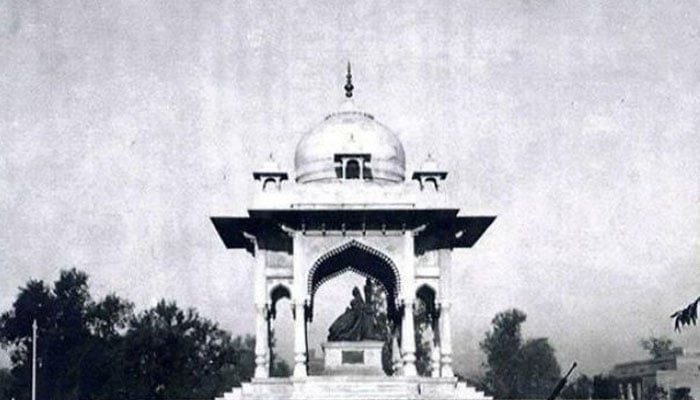

Pavilion

Lahore had remained more or less confined within the boundaries of the Walled City until the advent of the Imperialists. By the turn of 20th Century, the city had sprawled outwards and to the east into what was known as “Donald Town.” A “Charing Cross Scheme” of 1913 for the eastern outskirts of Donald Town reveals a plan to enclose a garden at the juncture of the Mall, Egerton, and Montgomery Roads, with a pavilion designed by Bhai Ram Singh, hosting a bust of Queen Victoria.

Queen Victoria statue in Lahore Museum

After Partition, the people of the newly independent Pakistan decided there was no place for the bust of the Imperial Queen in their city. It was relocated, with the help of a donkey cart, to the Lahore Museum, where it stands as an amusement and reminder.

Masonic Lodge

Shah Din Manzil

In 1914, Basil Sullivan, a consultant architect to the Government of Punjab, prepared an improvement plan for the Charing Cross. Sullivan added a semi-circular strip at the bottom of the garden and made provision for the Masonic Lodge and Shah Din Manzil to mirror one another. The two buildings at the south of Charing Cross were constructed by 1916, although renovations in the past decade make them dissimilar to one another.

It took Charing Cross nearly another 60 years before it was enclosed as it is today.

Punjab Assembly

The Punjab Assembly was constructed by 1938 and was the site of many of the Quit India protests that political Lahoris were so passionate about. Lala Lajpat Rai’s fiery speeches were often given at the steps of the Assembly. His murder at the hands of the Imperialist-controlled Punjab Police inspired Bhagat Singh into revolutionary action.

The rest is the stuff of legend, not even a century old.

In the mid-2000s, the Pakistan Muslim League (Q) government decided to expand the assembly building complex. It is still not complete.

After the spate of suicide bombing attacks in Lahore in 2008-2010, the Assembly Building was closed off by a wall. The people today are separated from their representatives in the name of security.

Alfalah Building

WAPDA headquarters

The Alfalah Building was constructed by 1964 with funds raised from Government Servants’ Benevolent Fund. It was designed by J.A. Ritchie and at a height of 72 feet – a full five floors – was considered at the time as one of the city’s tallest “modern” buildings. The headquarters of the rapidly expanding Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) was designed by Edward Durrell Stone, and were completed by 1967 on the site of the old Mela and Jodha Mal Buildings.

Summit Minar

The Summit Minar in the centre of Charing Cross was designed by Vedat Dalokay and was commissioned to commemorate the 2nd Islamic Conference – the largest gathering of Muslim leaders in history – held in Lahore in 1974. Completed in 1977, rising to a height of 170 feet from a pool of water, it is meant to symbolise the unity and brotherhood among Muslim states.

Few know Dalokay designed the Minar as a dynamic open space, including an underground museum, gallery, and conference hall. I wonder if the recent suicide bomb blast left the Minar, or its symbolism, damaged.

Having spent most of its life part of a Pakistani city, Charing Cross is nevertheless an instant reminder of the multicultural and rich political history of Lahore. In terms of space, it is often a congested intersection. At the same time, it reflects the Sikh and Colonial heritage of the city, the violent political upheavals it has faced, and the incredible urbanity and sophistication of its citizenry.

The Lahore High Court, in its recent decision granting a stay against the parts of the construction of the Orange Line, declared our cultural heritage as part of our Fundamental Right to Life.

This precedent-setting decision has not been properly celebrated. It reminds us that proper enjoyment of this right is not just in the preservation of our built environment, but in acknowledgement of the richness of our shared and multicultural history as well. Charing Cross reminds us of the violence Lahore has so often faced. And it shows us that, just as in the past, we can heal our wounds.

Ahmad Rafay Alam is an environment lawyer and activist.