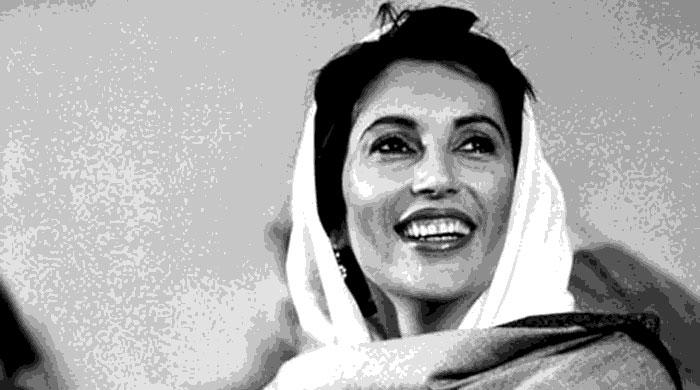

Benazir Bhutto’s politics of resistance and reconciliation

The younger Bhutto’s political journey, spanning the 30 years from 1977 to 2007, is full of courage and sacrifice

December 26, 2020

In 1981, Benazir Bhutto was arrested from the residence of former deputy speaker National Assembly Dr Ashraf Abbas and escorted straight to a lock-up in Central Prison Sukkur.

The daughter of a former prime minister, she was held on suspicion of aiding her brothers in the hijacking of an aircraft. She had nothing to do with it, but Benazir was nonetheless kept in Sukkur for five months before being shifted to Karachi.

A retired police officer once told me on the condition of anonymity that at the prison, the 28-year-old was housed in 'C-Class' jail facilities by the authorities.

“That year, [Benazir] was kept in one of the worst cells in one of the worst prisons in the province,” the officer said. “We were instructed to keep her in a cell from where the jail staff and other inmates could see her at all times, to, well, further humiliate her.”

The younger Bhutto’s political journey, spanning the 30 years from 1977 to 2007, is full of such examples of courage and sacrifice.

But while she was not afraid to take a defiant position, Benazir also did not shy away from the possibility of reconciliation. An example of this is when, in 1988, she decorated Gen Aslam Beg with the "Tamgha-e-Jamhuriat” for holding elections and not imposing martial law after General Zia’s death.

Even the former chief of Inter-Services Intelligence Lt Gen Hameed Gul admitted that he had misjudged her when she returned on April 10, 1986. The impression was that she would immediately mount a path of revenge, “But when I met her for the first time, I found a true patriot in her,” Gul told me during an interview at his residence.

Her critics claim that Benazir was a product of the establishment, when in fact she was always in the crosshairs. Though she attempted to reconcile and move forward, the powers that be played against her on multiple occasions.

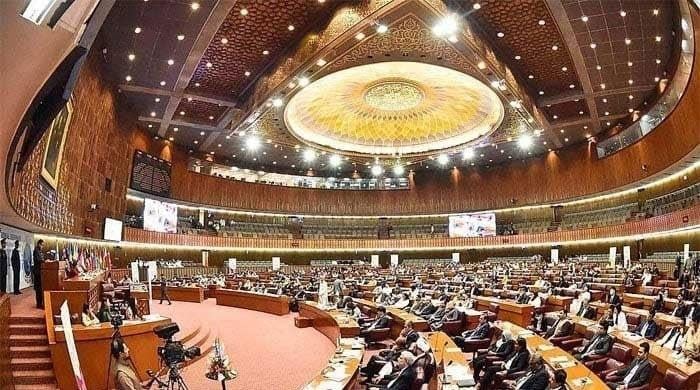

In 1988, they gathered politicians opposed to Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and formed the Islami Jamhoori Ittehad — a right-wing alliance of conservative political parties — to ensure that the PPP did not get a two-thirds majority in parliament.

When her party still managed to win the polls, they only allowed her to form a government on the condition that it would continue to support and keep President Ghulam Ishaq Khan in office. Finally, in 1990, her government was sent packing.

Back in 1981, when Benazir Bhutto was accused of playing a role in the hijacking, the authorities used the ploy as political mileage against the PPP and the recently-formed opposition alliance, the Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD).

As a consequence, one of the parties in the MRD, the Muslim Conference headed by the late Sardar Muhammad Abdul Qayyum Khan, quit the alliance, forcing the MRD to delay its movement by two years.

Like her father, former prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, she too made mistakes. One of these was to accept power with conditions in 1988, mentioned earlier. Her second error of judgement was when she came to an agreement, known as the National Reconciliation Ordinance (NRO), in 2006 with then military dictator Pervez Musharraf

Often, when I met her, we would argue over why she took these decisions. Her reply: “In 1988, I could have turned down the offer, but I thought, and I could be wrong, that my party workers had suffered far enough under the dictatorship of Gen Ziaul Haq.”

With regards to Musharraf, she would add that she only agreed to the NRO on the condition of a free and fair election. Regardless of what the deal was, she broke it when she announced her return to Pakistan.

A committed politician

Throughout most of her life, Bhutto remained a committed political worker. When in exile during the '80s, she threw herself into organising her father’s party, visiting workers in hiding and organizing underground meetings. Nothing could stop her, not even detention. When it came to sacrifice, she led from the front.

Once, in 1986, when she announced that she would lead a rally from Lyari in Karachi, the police surrounded her home. PPP supporters waited outside, unsure if she would be able to come out. She escaped with the help of a friend and later emerged from the residence of a party activist, the late Ayaz Samoo.

One PPP worker from the 1980s, Masroor Ahsan, who later became the president of PPP Karachi Division, told me that Bhutto would meet workers in hiding and give classes on how to write effective slogans.

Another PPP worker, Sheikh Allauddin, revealed in his book that after the second arrest of Z.A. Bhutto, Benazir and her mother came to the PPP’s old secretariat and asked the party to respond.

There were 50 workers in the room, Allauddin recalled, who decided to organize a protest immediately. But the local leadership refused to come out of their homes.

Disappointed, they turned to Benazir for guidance. That night, dressed in a burqa, she met them at a secret location. She told them to go ahead with the protest without the leaders present.

Another defining moment of her career in those days was the 1980 trial of leaders of the Communist Party of Pakistan, who were arrested on sedition charges. The men were tried in a military court.

It was a rare case, where over 50 leading politicians, intellectuals and writers appeared as defense witnesses. These included Benazir Bhutto, Abdul Wali Khan, Mir Ghous Bux Bizenjo and Meraj Mohammad Khan.

As a reporter, I was covering the proceedings. The day Benazir Bhutto was summoned to appear, police cordoned off the entire area of the court. But the BBC correspondent, Iqbal Jaffery, managed to slip inside and hear some of the initial questions Benazir Bhutto was asked. When the court asked her about her cast, she replied: “I don’t believe in casts.” For the first time since her arrest, Benazir Bhutto’s voice was aired on BBC.

Benazir was without question Pakistan’s most outspoken and courageous leader, but what happened to her legacy after her assassination in 2007 has been weighing her party down ever since.

Why, one wonders, did the party compromise and agree to work with those who she suspected of trying to kill her?

Abbas is a senior columnist and analyst with GEO, The News and Jang. He tweets @MazharAbbasGEO