China develops ultrathin flexible, stretchable fibre chips that compute, communicate

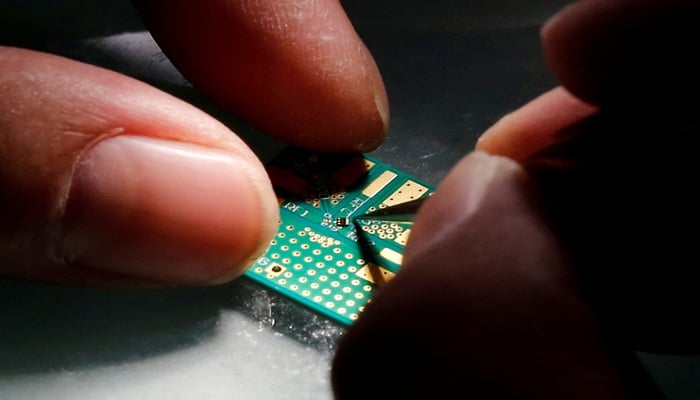

innovative fibre chips are actually integrated circuits embedded within ultrathin, flexible fibres

January 24, 2026

In a development testifying to China's unmatched prowess in computing and chip-making, Chinese researchers have developed chips that look like tiny fibres that can compute, communicate, and be woven into fabrics or high-tech devices.

These innovative fibre chips are actually integrated circuits embedded within ultrathin, flexible fibres, signifying a groundbreaking advancement in electronics.

The development, published in the journal Nature, marks the beginning of a transition away from traditional rigid silicon chips and could revolutionise wearable technology, medical devices, and human-machine interfaces.

The team of researchers was led by Peng Huisheng from Fudan University in Shanghai and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The team accomplished an incredible feat after spending nearly a decade integrating processing, memory, and signal-handling circuitry into fibres thinner than a human hair.

They achieved an impressive density of around 100,000 transistors per centimetre, rivalling the performance of conventional chips while maintaining full flexibility and stretchability.

The innovation's core is a multilayered internal architecture that places circuitry throughout the fibre, rather than just on its surface.

This approach enables the use of nanometer-smooth polymer substrates, which can be spiralled into complex configurations, addressing fabrication challenges associated with flexible materials.

Laboratory tests of the fibre chip demonstrated capabilities for digital and analogue signal processing, as well as neural computing functions.

The surprising fact is that these fibres can stretch up to 30%, twist 180 degrees per centimetre, and remain functional even after over 100 wash cycles.

They can withstand temperatures up to 100 degrees Celsius (212 degrees Fahrenheit) and support the weight of a 15.6-tonne container truck.

The team succeeded in placing power supply, sensing, computing, and display functions into a single fibre, eliminating the need for external chips in smart clothing.